Intervention

I've written before that I see the brain mostly as an association machine. But there's a problem with that: associations are a runaway self-reinforcing mechanism. A dog jumps on you as a kid and you get scared, building a scary association. Then when you see another dog, you get scared again before you even get near it, which strengthens the association even though nothing happened. This continues until somehow you end up with a runaway fear of dogs from just one incident.

This problem can be particularly pronounced when motivating yourself to work on something. You think about doing it, but you don't do it – not even necessarily for a good reason, maybe you just got distracted or you were too tired that day or something. Regardless, an association forms between thinking about the work and not doing the work. Every time you think about doing the work but don't do it, it's more difficult than the time before. This aversion seems like it's coming from nowhere because, in a sense, it is; it's just a feedback loop amplifying meaningless noise.

Despite this, we manage to get things done and break these cycles thanks to our executive function. We can deliberately override what our association machine would do by exercising cognitive control over our behaviour. So we compel ourselves to work on a project even though we don't feel like it, because we know that we will enjoy it once we break out of this pattern of never starting. We compel ourselves to pat the dog even though we're scared of it, because we logically know the dog is friendly and our fear is unfounded.

But it is also possible to abuse executive function. You can use the same mechanism to compel yourself to do something that will not build a good association. Instead of using cognitive control to work on a fun project you've been putting off, you could use it to compel yourself to do work that you don't actually enjoy. Either way works the same at the time; you're just overriding those bad associations. The difference comes later; doing the thing you enjoy builds a good association, doing the thing you don't enjoy reinforces bad ones.

Over time, abusing your executive function like this leads to a stronger and stronger negative association. After all, you can choose to keep slapping yourself in the face, but you're not going to start thinking it's fun. Repeated exposure to these negative associations can lead to learned helplessness and depression. Worse still, there's evidence to suggest that your cognitive control has a limited capacity that depletes as you use it. So you could end up in a situation where you are depressed but also lacking the cognitive resources to do anything about it. I believe it's these two things together that we refer to as burnout.

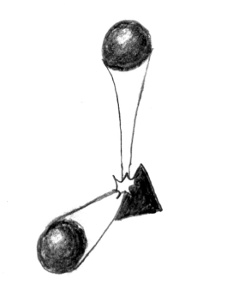

For this reason, I think it's important to be selective with your use of executive function. It's not something that should be needed constantly, or used to prop up a negative situation through sheer force of will. Instead, your association machine should be allowed to do its job, which it mostly does very well. When it gets off track, your executive function can intervene, make some adjustments, and then step away again.