Nymphicus hollandicus #3

Much like a person, an operating system needs to multitask. It can only do one thing at a time, so when you ask it to play music while you edit a document and a webpage loads in the background, it needs to find some way to split up those tasks into small pieces and structure them so that everything happens smoothly. This is called scheduling, and it remains a tricky problem even after half a century of operating system development.

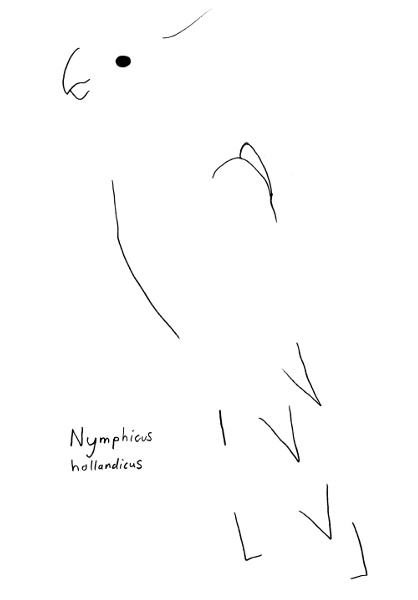

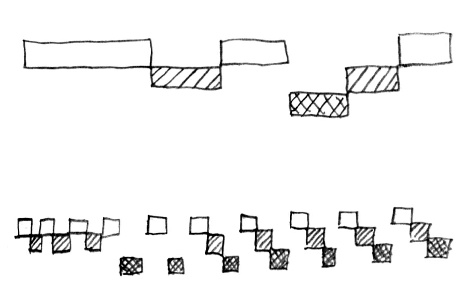

These days, most schedulers are preemptive, which is to say that the operating system decides how much time each task gets before cutting it off and moving on to the next task. However, there is another, earlier model called cooperative multitasking. In the cooperative model, the tasks themselves decide how long they should take. This is simpler and more efficient, because instead of being cut off right in the middle of something, your tasks can run uninterrupted until a convenient stopping point. The drawback is that one bad task could take too long or never hand control back, leaving the whole system laggy or stalled completely.

The way we manage our own time has a similar tradeoff. You can only work on one task at a time, so you need to find some way to schedule all the things that come in. Traditionally, this scheduling is preemptive: someone comes by your desk, calls you, messages you or whatever to ask you to do something. You stop what you're doing, respond to their task, then return to your own task. Lately, in recognition of the costs of preemption in terms of focus and efficiency, many people have been moving towards a more cooperative model, where instead of being interrupted mid-task, you take breaks at the end of a task to check for messages.

In stark opposition to this is the rise of notification systems. These have become hugely popular, originally on mobile but now on desktop too. With notifications, every app can preempt you whenever it wants your attention. Why did we decide this was a good idea? Well, I'm not convinced we did. Rather, I think tools have an incentive to interrupt us more often because they get more activity that way. You can see the extremes of this in the way that mobile apps now invent new and useless categories of notifications so that they can appear on your screen more often.

I'm beginning to think the only solution to this is to turn off notifications entirely, or at least leave your phone on a do-not-disturb setting and only check it when you're not doing something else. It'd be great if there was an option in current notification systems to support this, where it would collect activity for you, but only show it to you when you ask rather than interrupting you in real time. These would be cooperative rather than preemptive notifications.

That said, there are the same drawbacks to the cooperative model for us as there are for operating systems. Checking less frequently increases throughput, but decreases responsiveness. Depending on how long it is between tasks, you can end up missing things that actually do need to happen in real time. And, if one of your tasks ends up taking way longer than you expected, it can bring everything else to a halt.

So perhaps there is still a need for preemption, but not nearly as many as the real-time notification orthodoxy would have you believe. At the very least, it would nice to have a hybrid model with some separation between notifications, which demand immediate attention, and activity, which is just some things that have happened and you might want to know about.

There's a funny thing about starting something. Sometimes it seems like you just decide what to do, sit down and do it. Other times, it seems like just about everything else in the world has to happen first. You go to start, but you check your email first, and then you remember you should really respond to a friend who wrote to you a while ago, and then you remember you have some chores to take care of, and because you don't really want to do them you go check Facebook or whatever...

I think it's worth analysing this notion of the time or effort between deciding to do something and actually doing it, which I've been thinking of as impulse. Having a high impulse means you can almost immediately go from thinking about something to doing it, and having a low impulse means it tends to take a long time or a lot of effort.

Low impulse is often caused by intrinsic things. For example, if you tend to think of ideas and then shut them down, eg "that'll be too hard", "it won't be good enough", "I should do other things instead" and so on, then it's easy to build an association between thinking about things and not doing them. If you're easily distracted, you can have the opposite problem, where you think of something but before you do it you start thinking about something else. Or if you're disorganised or busy you might get too used to responding to external impulses and forget to make use of your own.

External causes of low impulse often look like interruptions, where in between thinking of something and doing it, someone bothers you with their own needs. Alternatively, if you have a long list of stuff you should be doing, then that tends to intrude in the space between thinking and doing. Similarly, if your tasks are highly dependent on each other then before you start on one thing you have to think about its consequences on everything else, leading to an enormous amount of inertia.

I firmly believe we naturally exist in a high-impulse state, but we add complexities that drag our impulse down and make us less creative and more hesitant. The solutions then, are mostly about recognising the things that decrease your impulse and removing or restructuring them. In the case of the intrinsics, that means reducing distractions and building more positive connections between thinking and doing. In the case of the extrinsics, it's mostly about decreasing these forms of interdependence and state that restrict our actions.

None of which is to say that high impulse is always the stated goal. After all, if you're in the middle of a righteous writing marathon and you have a stray idea, it's probably best to just note it down and leave it for later. That said, I think there's always a risk of putting our ideas off too much and ending up in a low-impulse mindset, starved of the vital creative connection between thought and action.