Last week I made 1 prototype, and this week I made 1 again. I feel like I'm on a better track with this one, because it was a more prototype-appropriate size. I wanted to do a few more, but other things kept getting in the way, mainly catching up on writing which I've now done. I did some good work on a small project, in line with my recent plan to avoid recruiting prototypes for project work. I think these two factors will lead to more prototypes soon, but we'll see!

This was a simple element toggler that I used for Concentrate to toggle the article back and forward between regular and concentrated mode. It was super simple, so I figured I'd just write it in straight Javascript instead of using any fancy stuff. Worked out pretty well, I think. It's nice when my prototypes and writing can complement each other, as in Fibonacci's Infinite Sequence. I'll have to keep an eye out for opportunities to do that more.

I've been thinking a lot recently about feedback systems, in terms of failures and other signals to focus your attention, and also in terms of frames of reference that you can use to measure your progress (or lack thereof). I think the defining quality of any feedback system is that it gives useful feedback, where I would define useful as effectively partitioning the action-space.

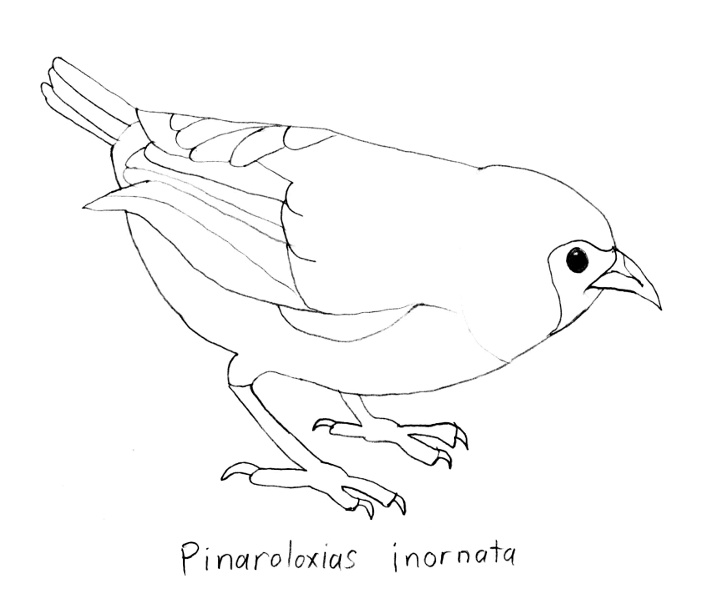

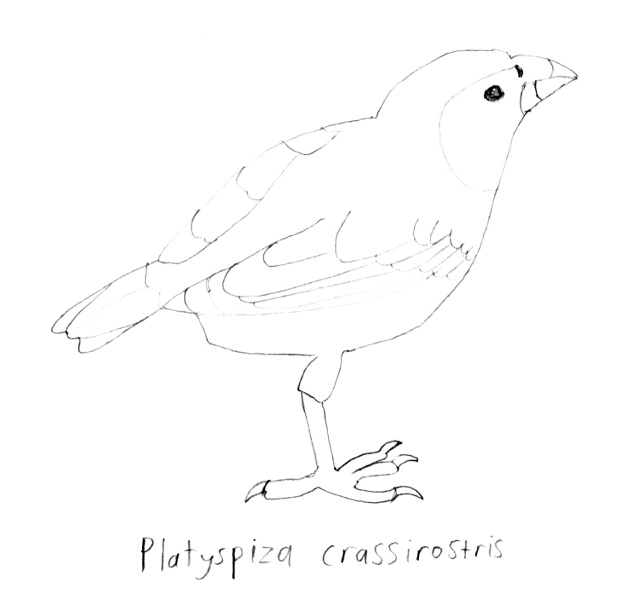

I covered a similar concept, partitioning idea-space, in an earlier post on strong and meaningful statements. Much like a space of ideas, you can imagine there being a space of all actions, and you want to reduce that space to a manageable set. Your feedback system should act like a knife cutting into the cake of all possible actions, separating the good actions from the bad ones, and ideally separating the most possible actions with each cut.

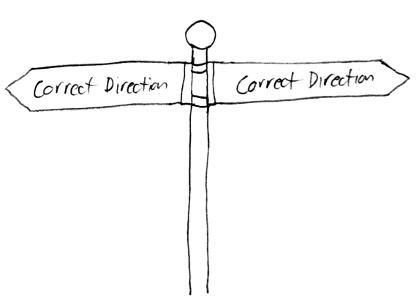

My recent situation of being in a semi-permanent state of behind with my posts is an example of feedback that isn't useful because it doesn't partition the action space. All that signal can tell me is "you're still failing". It can't effectively partition my actions into ones that have led to failure and ones that have led to success because they all keep leading to failure. Conversely, though, a feedback system that is always nice to you is just as useless. Instead of saying you're failing all the time, it says you're succeeding all the time. Either way it can't separate your actions from one another.

Always being right is more tempting than always being wrong, for mostly egotistical reasons. There's also an implies both ways problem: improving means you get to be right, but being right doesn't mean you're improving. It's easy to accidentally put yourself into a situation where all your signals are necessarily green. Everything's going great! Your actions are definitely still the correct ones!

But it's important to bring it back to this idea of useful feedback, of meaningfully partitioning some actions from others. If your feedback is no longer doing that, it's stopped being useful feedback. If you want to make better decisions, you'll need to find better feedback, to expose yourself to harsher standards or more difficult problems. It's possible to always be right, but only at the cost of being unable to improve.

I think it's better to be wrong some of the time.

A year ago, I wrote Mood days, about the benefits of letting your plans adapt to the mood of the day. I've since written some fairly contradictory things, including Output/input, where I argued that it's your actions that most strongly dictate your mood (and your future actions). The truth is that I am somewhat conflicted about these two ideas, which both seem true to me. I think the key is how much to expect and value consistency.

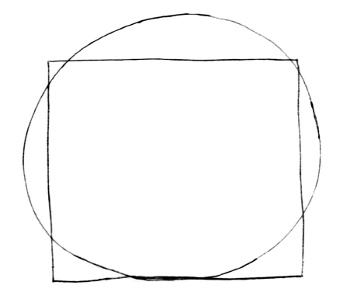

One of my favourite articles is a piece by Venkatesh Rao about legibility, the idea that certain models are considered preferable because they are easier to understand and manage, even if they don't accurately reflect the underlying reality. In What a piece of work, I argued that we shouldn't think of ourselves as divine messengers of logic and reason, but rather apes with shoes who have to work exceptionally hard to achieve anything approaching effectiveness. That is, I think our underlying reality is the monkey brain, and the model is our plans and systems.

In that sense, I think this tension of legibility is really the core problem. I have come to immensely value habits and stability as a way to overcome monkey-brain problems. I know that some days I won't feel like writing, or programming, or doing anything useful, and I know that at those times my habits can act as a kind of Higher Power, something that you can trust when you don't trust yourself. And yet, there is some inevitable sense in which by forcing yourself to accommodate to habits and consistency, you are ignoring the underlying reality in favour of legibility.

In The stability tradeoff, I wrote that instability is also a fundamental part of creativity. Valve Software, for example, is notoriously lacking in structure. The company org chart is either a flat line or a giant spaghetti mess depending on who you ask. Employees get to choose what to work on based on what they feel like at the time, their desks even have wheels so as to encourage frequent movement. Instability! Chaos! Madness! Yes, but also creativity. The company fails in predictable ways because of their lack of structure, but also succeeds spectacularly: 4 of the top 10 games on Metacritic were developed by Valve, including number 1.

So do you follow Valve's lead and make your system the most humane, the most reflective of the underlying chaos of creativity? Or do you instead try to adapt yourself to the system, try to be more consistent, more predictable, more manageable? In Creation and creativity, I argued that you need both to some extent, but that doesn't necessarily help with any particular decision. You're feeling scattered today, do you fight to stay focused or just go with it?

The truth is I don't know yet. The best I can say is that consistency has helped me, and that right now I would try to shape the mood to the actions rather than the actions to the mood. That said, it could change. Maybe the whole thing is one big simultaneous equation where you need to optimise for both at once. I'm not sure, but I am hopeful that there is an answer out there. Finding it would be a significant contribution to both productivity and creativity.